While English language education was once practically forbidden, decades of reform have turned it into massive business

As the daughter of an English teacher in rural China, I spent my formative years plunked on the floor by the door of her classroom, listening as the room thundered with slogans like, “Long live Chairman Mao!” or “I am a Red Guard!”

When I thought back on this scene years later, I realized that those students probably never had the chance to use any of those sentences. Except for one—a quote from Karl Marx that remains true to this day: “A foreign language is a weapon for the struggle of life!”

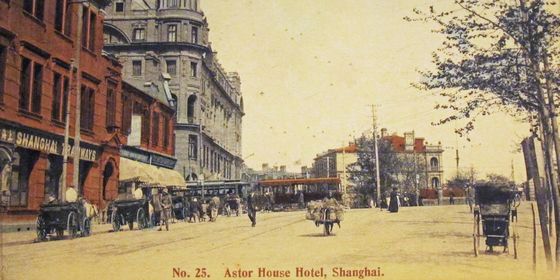

In China, this was true as early as the 1940s. When my grandfather was hunting for a job, he learned a popular rhyme to cope with interviewers who asked questions or demanded answers in English: “Diantou yes, yaotou no, lai shi come, qu shi go, yige dayang one dollar, ershier sui, twenty-two” (Nod for yes and shake for no; know the difference between come and go; you want one dollar for salary, and you’re 22 years old). With the help of this formula, he got a job as a Chinese calligraphy teacher and harbored a lifelong respect for English.

That respect did not stay with the rest of the country. By the 50s, Russian was ubiquitous and English was traitorous. Thanks to the Cold War, English had become known as the “imperialist language.” Most people during that time never once saw an English book; they were only sold by a specific department of the Foreign Languages Bookstore, and only to those with certain certifications. The situation changed after China’s relationship with the Soviet Union fell apart in 1956, and Russian gave way to English. Mao Zedong himself was said to be a most avid learner.

My mother was a product of this change. In 1973, after working on farms for five years, she was suddenly summoned for a college entrance exam. At the interview, she was told to read a few English sentences after a tape. Impressed by her articulate pronunciation, the testers promptly put her into the English department.