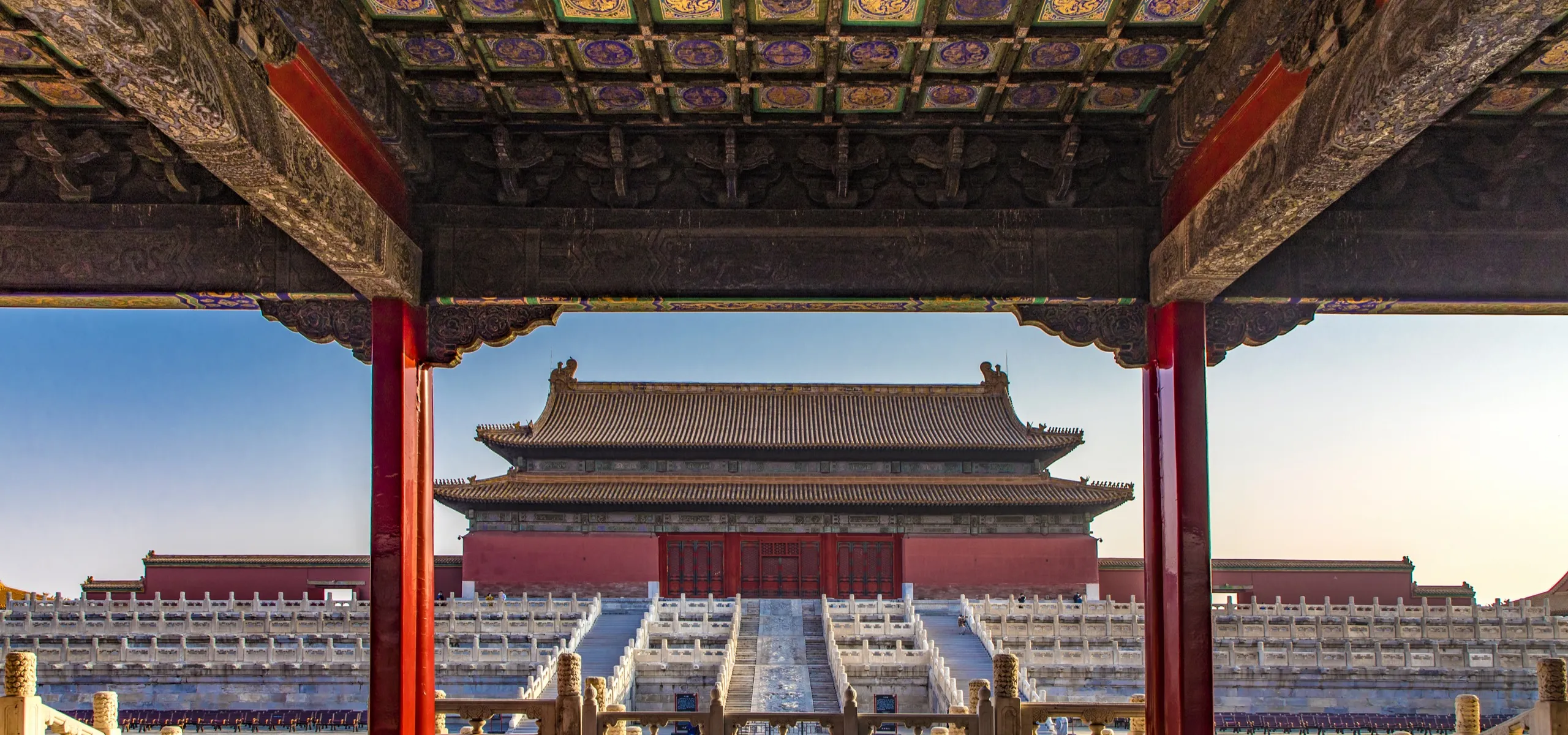

Arson, thieving eunuchs, military invasion: the Forbidden City’s journey from imperial palace to public museum was anything but smooth

When Zhu Di (朱棣), the third emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) ordered a grand palace built in Beijing in 1406, he probably didn’t envision vast crowds of commoners lining up to enter every weekend and public holiday, nor history buffs visiting the sprawling public museum inside.

The grand palace, which became known as the Forbidden City, was the exclusive residence of 28 emperors from the Ming and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties, and was a symbol of the supreme power of China’s imperial rulers. It became a museum in 1925, and is now one of the most famous tourist attractions in the country—probably much to Zhu Di’s chagrin.

The process of opening the Forbidden City to the public, which culminated in 1925, was arduous. The first proposal of building a “royal household museum” was put forward 20 years earlier, in 1905, when politician and entrepreneur Zhang Jian (张謇) wrote a memorial to the emperor, suggesting he establish a royal museum in Beijing, which could display objects collected by the royal family. “[A museum] could not only help protect the culture of the nation, but also benefit young students and scholars,” he wrote. According to Zhang’s blueprint, similar museums should be built in all the provinces, so that people all over the country could have access to these great educational resources.

However, Zhang’s appeal was rejected. Apparently, it was unimaginable for the rulers to allow ordinary people to gaze upon the royal collection.