Ten hours on China’s mobile public forum

2:30 p.m., Gubeikou. Train 4471, the daily service from Beijing to Chengde, stops at Gubeikou Pass in the Yanshan Mountains every afternoon. Rumor has it that it delivers fresh vegetables to a military police contingent nearby. It’s a step down from the thousands of soldiers who defended the capital against the Japanese here in 1933, and much reduced compared to the Ming dynasty, when the scraggy, sun-scorched ramparts of the Great Wall now overlooking the tracks had been the imperial army’s last stand before the Beijing city gates.

For the passengers, the doors don’t open and there’s no way to tell if you’re really riding with the border patrol’s greens. However, the few minutes the train spends here serve as a convenient visual reminder that you’re leaving Beijing and entering the province of Hebei. “We’ve ‘exited the frontier,’” says Mr. Dai, a construction worker seated to my right. He’s using an ancient term, chusai (出塞), which in modern Chinese retains all its evocations of exiled politicians, princesses married off to far-off tribes, and poor settlers setting forth into the unknown.

But for Dai it actually means the opposite. “Once you exit the frontier, you know you’re almost home.” And suddenly he’s smiling: “Finally.”

Gubeikou is just 140 kilometers northeast of Beijing, but we’ve been on the road since 9 in the morning. That’s an average speed of 25 kilometers an hour, one-fourteenth the speed of the Chinese rail system’s showpiece high-speed rail. Dubbed “green-skin trains” for their iconic forest green livery and yellow trim, trains like 4471 are, unsurprisingly, living on borrowed time in a country for which rail infrastructure has long been a matter of national pride.

Whereas China’s HSR network, the world’s longest as of three years ago, gains around 2,000 kilometers of track each year, four out of seven remaining green train services in the Beijing area were phased out at the start of 2017; 4471 is one of the only survivors—and even it has had its schedule reduced. Where these old relics are still found, rattling with carriages left over from the 1980s, they obey a protocol that the passengers sum up as, “stopping wherever there’s a station, standing aside wherever there’s a passing train.” We literally make way for modernity.

“Why are you on this train?” four young passengers sitting across the aisle (three e-commerce entrepreneurs and an accountant) ask me as soon as I sit down. Traveling with a camera, no luggage, and two foreign interns, I am cut out for the HSR’s air-conditioned interiors and plush seats. My new companions sport bright colors and collegiate-looking glasses that stand out sharply against the cream carriage walls and faded blue leather benches, the seat-back so perpendicular that it makes them hunch. I reply that I like old trains and cheap fares, and pose the question back at them. “All other trains were sold out,” they admit.

On a Chinese train you can tell a lot about the travelers simply from what they bring. My friends across the aisle, who are not here by choice, travel with hard-shell suitcases, ornaments on their phones, and a seemingly bottomless supply of dried convenience-store snacks that they bring out one by one. Dai the construction worker, who takes this train every month, brought sunflower seeds and a luggage trolley loaded with various-shaped packages wrapped in plastic bags for a short visit home.

Authorities are repainting new trains with green livery to “remind people of travel,” but few authentic 80s green hard-seat trains remain (Hatty Liu)

The baskets of fruit and monstrously large striped sacks belong to a riotous knot of workers seated in the back. Today is the first day of Golden Week, the only time apart from the Lunar New Year that most migrant workers in China get to visit home. They are a group of mostly strangers who’ve discovered they hail from the same county and are anointing their new acquaintance with beer, conversation, and a case of yellow apricots that someone has passed around.

This hasn’t changed throughout the decades on the green-skin train: On a journey of tens of hours, with no distractions but proximity to more individuals than perhaps any other moment in your life, the nation gets together to talk.

9:35 a.m., Beijing. By the time we crawl out of the North Fifth Ring Road, the crowd in the back are in full caucus led by a man surnamed Jiang who, beer in hand, has chosen a topic that perfectly parallels his swinging moods: money. “You can never buy a house in Beijing, a worker like you!” he shouts at another passenger. “Better come home and build a nice house.”

By the time I’m shuffled into their midst by way of the roulette-like seat-changes typical of a sold-out train, Jiang has started on the fields of wheat outside the window. “See that? Frozen to death. Farming is too expensive, that’s why I haven’t done it in 10 years,” he says.

Then he eyes the camera in my hand. “Are you a journalist? Forget Chengde, come to my village, we’ve got everything journalists want to see: houses falling down, paralyzed people on the bed…like my oldest brother, he’s a vegetable now because healthcare is too expensive.”

Across from me a woman surnamed Cao takes up the thread. “It’s so expensive to start a lawsuit,” she says, continuing an earlier conversation with Jiang’s sister-in-law, Ms. Tan. “You can sue all your life and never win, and then if the other side has money, they’ll pay someone to get revenge.”

Someone recommends contacting a TV station—“These days, the boss would never dare to withhold pay from migrant workers, because they’ll get exposed”—and when I’m shuffled back to Dai and our new seatmate, Mr. You, the two of them are complaining about the price of food on the train. “See that beer on the trolley? It’s 10 kuai. Even bottled water is 5 kuai. In the store you used to find beer for 6 kuai but it’s all 10, 15 now,” You says, and Dai replies, chuckling, “Instant noodles are still 6 kuai; it’s probably the only thing that hasn’t changed.”

The hot water is still free as well, warmed by the train’s 80s-era coal stoves that also heat the carriages in winter and make everyone’s noses itch.

The green train itself, it’s soon apparent, is the other exception to the everything-is-expensive clause to life in modern China. “We always take this train home, when we do go home,” Tan tells me aside, almost apologetically, as behind her, the crowd begins comparing their houses in the village have appreciated in value. “Time is no consequence, it’s cheap”— around 18 RMB to their hometown in Hebei, as in the 80s, but 110 RMB to go the same distance by HSR—“and that’s good enough for people like us.”

Attendants are responsible for selling food, checking tickets, and keeping order among the sometimes rowdy passegers; their mood visibly improves as the train nears its destination (VCG)

At one point in China’s recent past, this was, by necessity, good enough for everyone else as well. Commercial rail travel began in earnest in China after the 1978 reforms loosened the restrictions of the household registration (hukou) system and university education resumed after a 10-year interruption by the Cultural Revolution. Students and rural hukou-holders alike began flooding into Chinese cities to seek new opportunities.

However, with the reduction in state funding to several sectors of the economy, rail development included, it was estimated that Chinese trains in this period ran at 50 percent over capacity at all times—100 percent at peak periods.

For passengers this meant carriages crammed full to the doors, forcing ticket-holders to board through the windows while other long-suffering passengers attempted to push them back out. A trip from Beijing to Shanghai, five hours by HSR, could take 40 hours; passengers sat on the seat-backs and tables and slept under seats or on luggage racks, where farmers might also have kept chickens and pigs.

However, the overcrowded train carriage—crammed with disparate segments of the population, journeying for days on in the neutral hinterlands in between cities—was also a social space unlike any other at a time in China when collectivist ideals were being abandoned and the foundations for today’s wealth gap were laid. For all intents and purposes, there was (and is) just one class on the green train: tickets to a near-mythical “hard berth” class was always sold out or appropriated by those with connections, and everyone else, from student to entrepreneur to peasant-turned-migrant worker, did time together in the “hard seat”-class carriage.

As the generation that came of age in the post-reform era is fond of recalling, it was smelly, chaotic, and they wouldn’t want it back under any terms compared to the spaciousness and genteel calm of the HSR—but it was also a formative social experience, undergone collectively, made possible by people from many walks of life leaving home and leaving their prescribed social roles for the first time. No one with rudimentary people skills was without partners for card games or offers of food to share.

5:25 p.m., Naohaiying Station. A public space made up of diverse social interests, almost by default, becomes a political space as well. In modern China, where the “mass line” model of political participation has mandated that grievances be addressed to the Party and change to come only through the Party apparatus, it’s sometimes said that only three forums still exist where individuals can vent their criticism. Before there was the internet and the heated political debates that are reputed to take place inside the nation’s taxis, there was the train.

Coal stoves heat water and the interior of the train in lieu of air-conditioning—and cover everything, including the passengers, in a fine layer of soot (VCG)

Qing dynasty reformer Kang Youwei (康有为), in as early as the late 19th century, had singled out the railroad a major component in his ultimately failed proposals for “strengthening the nation”—it “lent itself to connecting language, likewise customs,” he wrote, and would lead to the “development” and “transmission of wisdom.”

Ironically, it would be in 1966, when the nation was on the verge of breakdown, that the railroad was first mobilized to a definite political aim. During the “Great Linkage (大串联)” movement of the Cultural Revolution, when Red Guards could ride the rails for free, millions of youths traveled to attend rallies in Beijing and then to “re-education” in the countryside. It presaged the travel boom of the 80s both in that it was the first time the post-1949 rail system saw significant ridership, and that carriage capacities were stretched beyond limit.

Packed in for days on end with their peers from around the country, Red Guards sang revolutionary songs, fought, and tried their best to study the masses they met on the train or saw outside, but they also traded stories, played cards, and flirted like youths away from home for the first time; as historian and former Red Guard Zhu Xueqin recalled in an essay, the overcrowded carriage gave youths of opposite sexes the ideal excuse to sit in each other’s laps.

As the student generation of the 80s grew up and grew rich side-by-side with the Chinese economy, now enjoying a great variety of train speeds, leg room, and privacy levels commensurate to their individual needs and achievements in the capitalist lottery, it’s the migrant class that has remained on the green train, and unclear what effect their discussions can achieve.

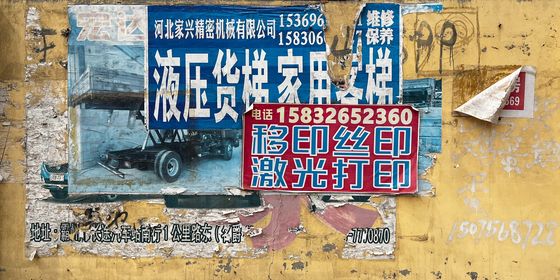

As we inch closer to the workers’ final destination of Longhua county, Hebei, the strident mood of the carriage as we exited the frontier dampened into a discussion of Su Laosan, literally “Su the Third,” a cult figure whose name only I appear to not know. He’s the host of Hebei TV’s rural channel, a folk hero who accepts people’s invitations to come and do exposés on their villages’ problems. Inspired by my camera, which turns out to be the most revealing object on this journey after all, they are wondering how they can get their stories told.

Tan doesn’t believe they can. “He’s just a hotline. You can call to complain, and he’ll send a journalist over, but you don’t know what will happen after that, what they’ll do ‘above,’” she says, referring by shorthand to the bureaucratic layers through which all national policy and funding, however initially promising, are filtered and diluted by the time it reaches their level.

“‘The sky is high and the emperor is far away,’” Cao quotes.

“It’s not the hard work that’s the problem, as long as they treat you right, you know?” Tan says after a pause. “You’re happy to work long hours”—or go home only twice a year—“when others are respectful to you, pay attention to your needs.”

Jiang, his son, and Tan all travel home from Beijing whenever their schedules permit—that is to say, just twice a year (Hatty Liu)

At a 30-minute stop at Naohaiying, a station surrounded by wheat fields near the end of the journey, we’re let out for a walk on the platform, and my fellow travelers discuss home prices again with Mr. He, the lone stationmaster. He seems pleased by the company for, as he tells me, we’re the only passenger train that stops here all day. “Not even the return train comes here,” he says, beaming.

In January 2017, three month after my journey, Naohaiying was removed from Train 4471’s schedule; no passenger trains now stop at the station in the wheat fields at all, and I wonder if the space for a spontaneous public forum in China has grown smaller still.

6:15 p.m., Longhua, Hebei. “It’s a good way to meet people, to unwind,” Tan says of the green train. “We started talking and found out we’re all from the same place, and we’ve been talking ever since.”

Perhaps only during peak periods like the Lunar New Year or Golden Week—when, as in the 80s, the green train might be the only choice—can you “meet” people on the train still: young entrepreneurs huddled over their screens until you draw them into conversation, someone with a camera who might be able to tell your story.

I had not sat down among the workers in the back for long before I’m asked for contact details. The few business cards I had are snatched up. “Maybe your village will end up on TV tomorrow,” Jiang jokes to each person in turn, though I’ve told him several times, I don’t work in TV. A woman sitting nearby, whom I’ve never spoken to, comes over and takes my last card, then hands it back after reading.

“Maybe it won’t make any difference,” Cao’s seatmate, a Mr. Li, suddenly pipes up. He’s holding the card and looking at me, though his phrasing is strictly third-person. “Even if we tell journalists what’s going on, and they put us on TV, maybe nothing will happen. Right?”

I think I’m supposed to contradict him.

At Longhua the train all but empties. The young entrepreneurs, Jiang, and the others file past me, and in the flurry of goodbyes, of everyone fetching their own luggage and calculating the taxi fare to their respective homes, they’ve all become like strangers again.

But before all of the passengers have gone, I look up, and the woman who returned my card earlier is back. Smiling slightly, and still without saying a word, she takes the last card from my hands and hurries out the door.

Malika Baratova and Camilia Jatahy contributed to this article

Green Train Blues is a story from our issue, “Wildest Fantasy.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.