When my father kicked me out, one of Chongqing’s “bangbang” porters took me in

1 / 8

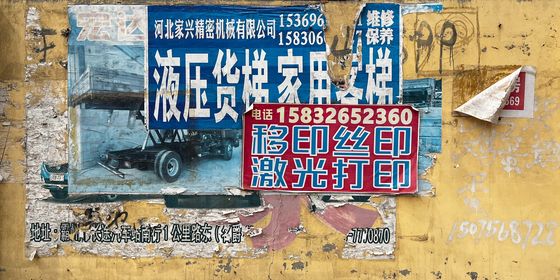

Just as I started junior high school, my father used all his savings to lease two storefronts in a newly-opened building materials market in Chongqing. The store specialized in aluminum ceiling panels, and other ceiling materials. He told me, “This store is the lifeblood of our family—your school tuition and all our basic needs depend on it. If we don’t manage it well, we’ll have to go back to our home village and work the fields.”

The two retail spaces totaled 200 square meters. They were originally connected, but my father split the space using several sliding partitions. We used the front as a showroom and the back as a warehouse. Once a customer had chosen a ceiling, my father would open the partition, drag out the 6-meter-long stock material, unpack it, and cut it to the customer’s specifications.

My father and stepmother ran the business on their own. When business was good, it got busy enough to make my head spin—it was common to have seven or eight groups of customers at a time. We lost many willing customers because there was nobody to greet them.

I helped out at the store every day after school and on weekends. But most of the time I could only play a supporting role: When it came to the planks and panels, the gratings and moldings, I was at a loss as soon as customers asked about the material, colors, or thickness.

Whenever this happened, my father and stepmother would stare at me blankly. Only after the customer left would they tell me the specs for the relevant ceiling or grating sample, rattling them off without caring if I understood.

The truth is that my heart wasn’t in it at all. I had just started at a new school. I had to deal with new teachers and classmates; I had lots of homework to do. My father didn’t seem able to grasp this. Every day when school got out, he’d have me rush over to the shop. I could only do my homework after we closed in the evening.

I once brought it up to him: “I have words and passages to memorize—I want to go straight home after school.” My stepmother just looked at me and laughed. My father also laughed for a while, finally saying, “You can come to the shop and do your work when it’s empty. If you don’t finish, you can do the rest when you get home.”

But in reality, I had to help my stepmother cook when we got home. After we ate and I cleaned up, only then was the time truly my own.

2 / 8

One Friday, when I went to the store after school, a 10-meter-long truck was parked outside. My father and a bangbang were unloading aluminum ceiling planks into the warehouse. I peered into the back of the truck and saw that there were still about 20 pieces left.

Bangbang is a Chongqing word for a porter. In the past, many travelers with luggage couldn’t handle our mountainous terrain, and some laborers from other regions saw a business opportunity in this. These porters got themselves carrying poles (biandan) or thick bamboo sticks (zhubang), and would tie all manner of bags to the poles. Once they had helped visitors carry their bags to their destination, they received payment. Because these laborers roamed all the alleys and streets of Chongqing, and because they carried zhubang wrapped in turquoise nylon string on their backs while they were waiting for work, they came to be known as bangbang.

Over time, bangbang became the general term for manual laborers in Chongqing. In the building materials market, many store owners would yell “I need two bangbang!” out the door when they needed help. But the people who came to work didn’t necessarily carry a pole with them.

My father told me, “This shipment is from Guangdong province, stop gawking and help carry it in.”

Then he turned to the bangbang, who was wiping sweat from his face with his hand, saying, “Bangbang, why don’t you take a break and drink some water.” Once the words left his mouth, he seemed to reconsider that form of address. So he handed over a bottle of mineral water and asked, “What’s your name?”

The bangbang took the water and set it aside. “People call me Old Tang.” He climbed back into the truck compartment.

I put down my backpack and rushed over to help him. He waved me off: “Get out of here, kid, what if I crush you?”

My father had always been strict with me. He had already told me to help, so if I didn’t, there were bound to be consequences. I ignored Tang and picked up an aluminum plank: “Even though this is 6 meters long, it’s not that heavy. We can each carry a plank at a time.”

He laughed, “You’re stronger than you look!”

As soon as the words left his mouth, I felt a rush of inexplicable affection—my father had never praised me like that before.

When we were finished, I sat down on a chair to rest. My stepmother handed Tang some cash before he even had a chance to wash his hands. He smiled and said “thank you” as he accepted the worn 10-yuan note. Because of the dust on his hands, he used only the thumb and index finger of his left hand to pinch the bill. He brushed his right hand off against his pants. When the hand seemed clean enough, he took the note and put it in his bag. He used the same method to clean his left hand and grabbed his mineral water: he was ready to go.

Before he left, he smiled and told my father and stepmother, “I’m leaving now, thanks boss, thanks ma’am. If you have work in the future, remember to give me a shout.”

My eyes were fixed on the unopened bottle of mineral water in his hand—he had sweated so much, wasn’t he thirsty?

After that, I frequently saw Tang around the market. He recognized me as well; whenever we got to talking, he’d say, “When your family’s store needs a bangbang, remember to come find me.”

The more we saw each other, the more I liked Tang. He was genuine and down-to-earth, and spoke at a moderate pace. From his smattering of white hairs, I guessed that he was around 50 years old. His skin was deeply tanned and starting to wrinkle, but he had the healthy glow of a lifelong laborer. Despite a slight hunch, he moved efficiently. Like the majority of bangbang workers, he smoked cheap Lanshan City cigarettes, but he didn’t reek of them.

The building materials market was huge and the laborers numerous; there was no shortage of competition. Whenever a store needed help, the boss only needed to stand outside the door and yell “Bangbang!” in any direction for seven or eight of them to come running up. Usually, the first two or three to arrive would snag the job. Some of the later arrivals would curse, while others seemed indifferent, their half-smoked Lanshan Citys still dangling from their mouths.

Tang generally wasn’t among the first two or three to show up. He didn’t seem willing to fight for work—when he missed out, he’d just fold his arms and joke, “Well, it looks like I’ve lost out again.” Then he’d wander off.