Viral app Douyin sells instant escapism to its viewers and producers—at a price

In 1968, artist Andy Warhol predicted that “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” Five decades later, 15 seconds is all it takes if you’re a Douyin user.

Chen Limei, alias “Heihe’s Kidney Sister,” was the ordinary owner of a barbecue stall at a night market in Heihe, Heilongjiang province, before she found accidental fame on the video-sharing app. Braving minus-30 temperatures and charcoal smoke, 28-year-old Chen and her husband often worked until 3 a.m., sometimes making only 100 RMB a night—hardly enough to provide for their 6-year-old son, let alone achieve the dream of owning their own BBQ restaurant.

Then, a seconds-long video of Chen warmly greeting a customer with a melodious “lai le, laodi” (“coming, brother?”) as she grilled her signature beef kidney slices, was viewed more than 5 million times on Douyin. Suddenly, the “Kidney Sister” had 1.3 million fans on the app, some of whom travel thousands of kilometers to Heihe just to film more videos with her.

Newfound fame brought Chen opportunities to perform in an internet film, appear on TV shows, and even start a restaurant with her cousin—but also a host of problems. The fairytale of an eighth-grade dropout becoming a beloved celebrity mirrors the meteoric rise of Douyin itself: As both viewers and creators seek an escape from the humdrum of everyday life, some find that the app can be more of a trap than a release.

Douyin (抖音, “Vibrato”), known as TikTok overseas, is a short video app launched by Beijing-based internet firm ByteDance in 2016. Within two years, it had acquired 250 million daily users, who reportedly watch a total of 30 billion videos each day. Creators compete to make unique 15-second videos using the app’s built-in background music, beautifying filters, and special effects, all with the hope of going viral.

Besides launching the careers of thousands of minor celebrities, the app has transformed obscure tunes into earworms, filled previously unknown restaurants with diners, and sparked “challenges” which have captivated the nation. Notables include the heartwarming “Four Generations” challenge (in which four generations of women of the same family appear in the same clothing) to the bizarre “Smash the Rice Wine Bowl” campaign by the Xi’an tourism bureau, capitalizing on a local tradition of throwing empty liquor bowls to the ground after drinking.

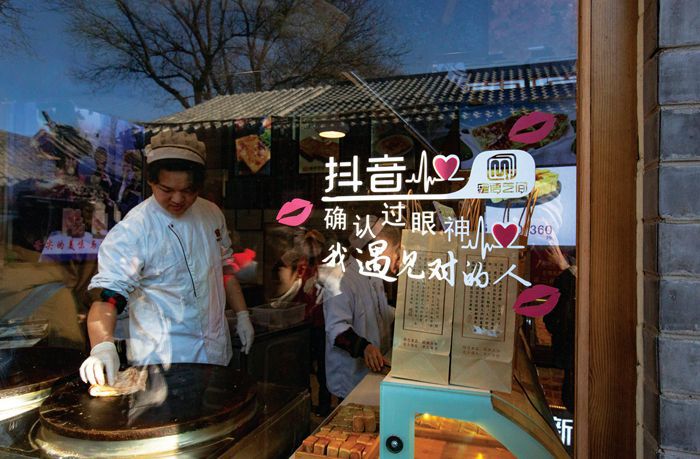

A pancake stand advertises the fact that it was featured on Douyin

With the motto “Record your beautiful life,” Douyin has differentiated from longstanding competitors such as live-streaming app Kuaishou, whose “Record the world and share your story” slogan resonates with the rural and working classes who still make up most of its user base, and typically broadcast scenes from everyday life.

Douyin’s earliest adopters were overseas returnees, media professionals, and models, according to Cui Jianying, a talent agent who now represents Heihe’s Kidney Sister. By producing higher-quality and more exotic videos, this “Instagram demographic” solidified Douyin’s reputation as an app for educated viewers. Sponsorship of popular shows, including The Rap of China and Happy Camp, added to its mainstream appeal.

However, as Douyin is trying to develop internationally, the Indonesian government banned the app in 2018 for creating “too much negative and dangerous content, especially for children.” In China, it has been criticized for giving a platform to false advertisements and adult content, and being addictive (Spanish newspaper El País dubbed it the “opium of the 21st century”). Chen Cen, a 29-year-old Shenzhen HR manager, realized that she had a Douyin problem when she missed a doctor’s appointment while glued to the screen; though the videos made her “happy,” she felt compelled to uninstall the app from her phone.

Douyin’s appeal, as well as notoriety, arises from its algorithm, which customizes feeds to a user’s interests. Users can sink hours into watching 15-second videos, spurred by an addictive Tinder-like interface which allows them to quickly swipe from one clip to another.

Chen Cen later reinstalled Douyin to stay up-to-date with her colleagues. She disagrees with the “opium” comparison, believing that her initial obsession was typical of first-time users: “They want to explore Douyin and get to know everything that is popular on the app. Once the customized feed kicks in, it becomes much easier to control.” To combat criticism, Douyin rolled out an “anti-addiction” notice that pops up when users have spent 90 consecutive minutes in the app. Watch for more than two hours in a 24-hour period, and the app automatically logs users out and requests their password again.

Li Jiajia, a 25-year-old English teacher in Yuncheng, Shanxi, is not fazed by these warnings. “It’s only recreation, and helps me relax in my spare time,” she says of her daily three-to-five-hour binges. “I can watch videos about places all around the globe, and understand the world a little more.”

Tourist sites documented on Douyin often go viral

Indeed, there are a plethora of travel clips that allow users to escape to beautiful areas around the world for a few seconds: flying with tourists in hot-air balloons above Turkey; hobnobbing with models on beaches in Thailand; taking in breathtaking drone footage among Shanghai’s skyscrapers; and making daredevil swings over a 1,000-foot drop in Henan’s Fuxi Mountain.

Video-creators seek a different kind of escape. Jiang Tao, who calls himself the “God of Laughter” on Douyin for his infectious, high-pitched giggle, rarely watches others’ performances on the app. He’s busy making videos to get a following, so he can become a star and leave behind the rural poverty of his childhood.

In the early 2010s, Jiang frequently went on TV talent competitions. After appearing on Tianjin TV’s Only You, he landed a contract to produce his own show on streaming platform StormPlayer. Before opening his Douyin account in October 2018, Jiang also broadcast on Kuaishou, and claims that on his best day, he made 5,000 RMB via “virtual gifts”—cash donations from his 300,000 fans.

Although Jiang and his laugh are now followed by 800,000 Douyin users, the app’s lack of “gift culture” means that he must find other ways to monetize his singular “skill.” To that end, he self-produced a romantic comedy called Please Love Me—an apt title for a man seeking recognition from the masses—which only made 214,000 RMB at the box office, although it was shown on CCTV-6. Still, Jiang laments that he will not be a true star unless he can perform in movies that are not his own.

“Apps like Douyin allow people to voice their own opinions of the world,” observes well-known investigative journalist Sima Nan at a recent taping of a CCTV talk show with Douyin stars, including Chen Limei and Jiang. “Media used to be one-directional, with broadcasters and newspapers. Now, it is two-directional.”

In the course of the taping, though, Chen Limei reveals that she is already weary of her catchphrase, which she now utters upward of 3,000 times per day (also, thanks to the northern hospitality culture, her alcohol intake has skyrocketed).

“I am nervous about Chen Limei’s career,” admits Cui. Because of her socio-economic background, Cui believes that the Kidney Sister is naïve, and he wants to prevent her from appearing in commercials that could damage her reputation.

Chen already is concerned about the number of haters she has amassed. When interviewed by Sima, she tears up as she recalls comments that accuse her of forgetting her roots or exploiting her new found fame. “I don’t want to stay poor at the night market forever,” admits Chen, even as she insists that the price for her beef kidneys will remain at 5 RMB apiece in spite of demand. “Come visit me in Heihe!” she invites TWOC off-camera. “I will make it for you.”

“In the past, people admired heroes. Now common people can be heroes,” Sima Nan concludes after the interview. “Even if there is not a lot to admire about them.”

15 Seconds to Stardom is a story from our issue, “China Chic.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.