In one of China’s least populated forests, legends of a yeti-like “wild man” live on

“Wild Man, come out and reveal yourself to us!” Mr. Li bellowed into the quiet forests of Tianmen Mountain, located in Hubei province’s massive Shennongjia National Park. He turned and smiled mischievously. “Be ready with your camera,” he instructed. “If we get a photograph, we can sell it for 5 million RMB.”

Our destination was a cave where, according to local lore, the legendary yeren (野人)—a two-meter tall, red-furred “wild man,” sometimes referred to as China’s Bigfoot—used to live. Our guides from the forestry district office, Mr. Li and Fu Rao, had never trekked to this remote location before, so had little idea of what to expect. The cave itself—with its hidden crannies, 30-meter ceiling, and panorama view of the mountains below—turned out to be worth the hike, but there was no sign of its alleged former inhabitants.

Although less internationally famous than the North American sasquatch or its Himalayan cousin, the yeti or Abominable Snowman, Shennongjia’s yeren has captured local imaginations: Xinhua conservatively estimates the number of yeren sightings at around 400, though some say it’s well into the thousands—a testament, perhaps, to the millennia-old mythology of the yeren’s existence.

Zhang Jinxing searching for yeren with volunteers in Shennongjia (VCG)

Shennongjia’s isolated and mostly untouched karst mountain forests have long been a source of fascination—the yeren is mentioned as far back as the Warring States period in poet Qu Yuan’s “Mountain Spirit.” Fossil evidence suggests the area was once home to a prehistoric giant ape that stood as tall as three meters. Nowadays, the remote region is renowned for rare and endangered animals, like the clouded leopard and golden snub-nosed monkey, which helped it gain UNESCO World Heritage status in 2016.

Yet the most elusive of these creatures, the yeren, is arguably the one that provided the biggest boost to the local economy, with “wild man” tourism bringing a welcome revenue to these isolated parts. There has been some rush to cash in (there is even a brand of hiking boot called Yeren), along with a few small attractions, but Shennongjia bucks the tourist trend of cynical sites staffed by perfunctory disbelievers. Among its hamlets, modernity has not yet penetrated timeless beliefs in the supernatural.

Instead, one encounters a nuanced relationship between humans and nature, science and the search for the yet-unknown. Although larger than the state of Rhode Island, Shennongjia has only 80,000 residents scattered among its three townships and small highways. Many locals seem ready to believe in the yeren because, surrounded by unutterable beauty every day, it’s easy to believe in nature and all its mystery.

At Songbai Township’s Natural History Museum, 23-year-old local Wang Yuling offers a personal tour. Besides a mother and her toddler, we were the only visitors. “This is our off-season,” Wang explained. “During the summer, we can have upwards of 1,000 people per day visiting.” Many of them come just to see the museum’s infamous “Wild Man Room.” The highlight is a life-size model of a female yeren, whose furry features resemble a Neanderthal from science textbooks rather than popular depictions of Bigfoot.

There are also illustrated posters, in both English and Chinese, relating some of the most exciting recent encounters with the yeren: farmer Xiao Ren, who accidentally encountered two yeren copulating in 1993; hunter Cai Yuetian, who claims to have been abducted by a female yeren, who then killed a tiger to protect her new “husband”; and the time that Kuomintang troops caught and executed a yeren in 1942.

“There is bound to be one,” surmised Wang, after looking at the museum’s evidence, which included fossilized yeren footprints. It was a sentiment that was repeated frequently during TWOC’s visit, with varying degrees of certainty: Some substituted the surefire “肯定有” with the more diplomatic “可能有 [there might be],” but no one expressed any doubt that something unknown lived in these misty peaks.

Skeptics suggest this is simply a scheme to boost interest in the national park. Paleontologist Zhou Guoxing, former director of Beijing’s Natural History Museum, is one. In 2012, Zhou published a disbeliever’s manifesto, “Fifty Years of Tracking the Chinese Wild Man,” declaring he had found no evidence of the yeren’s existence in all his decades of research, field studies, and interviews; most eyewitnesses could not even agree on the description of the creature they saw.

If the purpose of promoting the yeren’s existence is simply exploitation, though, the locals seem slow to take advantage. The unashamed cash-in trade, ubiquitous at so many Chinese sites, is largely absent; there are no Bigfoot toys (though one can buy a stuffed panda or snub-nosed monkey), no Bigfoot exploration coach tours, nor theme parks, other than a few museums (free with entrance to the park), with one offering a “haunted maze” filled with lurking wild men and loudspeakers emitting bestial shrieks; for 10 RMB, one can pose with a man in a yeren suit.

The author poses with a man in a yeren costume

Researchers, though, have generally taken the subject seriously (even if it’s to disprove a sighting), perhaps because so many of the sightings have come from supposedly reliable sources, from soldiers to party members, rather than uneducated peasants. Even government engineers have glimpsed one: A placard alongside the Tianyan Scenic Area marks the spot where a dozen specialists from the Ministry of Railways reportedly encountered a yeren while visiting in 1993.

Adding to the credibility is the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the country’s top science institution, which launched the only state-backed expedition to investigate the rumors in 1977, after a local deputy director, Chen Liansheng, claimed that he and several colleagues had spotted a beast (“covered in red fur…face human-like, with upright ears and a protruding mouth”) blocking the road while returning from a conference early one May morning. The expedition was ultimately inconclusive, and was perhaps doomed to failure, as much of the search was conducted during daylight hours by large, noisy groups.

If the example of the Tibetan yeti is any indication, though, deeper scrutiny usually brings disappointment for monster-lovers. The upright Himalayan biped called the metoh-kangi in the local language, or “man-bear snowman,” has captured the public imagination ever since British explorer Charles Howard-Bury reported seeing one crossing a glacier in 1921. Most recent scientific explanations, though, state that all the physical evidence, and therefore sightings, points to two species of indigenous bear.

Zhou, the Beijing paleontologist, also believes that the “strange footprints” found around Shennongjia most likely belonged to a bear. In his 2012 paper, he dismisses hair samples as belonging either to a wild boar or a human hoaxer.

At the area museums, much of the discussion about the yeren is couched in academic terms. While the Natural History Museum at Songbai takes an anthropological view, exhibiting oral histories of the legend, exhibits on Guanmen Mountain and Tianmen Mountain delve deep into the science, with the latter claiming to “seek the missing link in the process of evolution.”

For the new Natural History Museum at Guanmen Mountain, an introduction to infamous yeren is a means to promote the diverse flora and fauna of the region. With over 3,700 unique species of plants and 4,300 different types of insects, Shennongjia is home to various protected species, as well as an unusually large number of albino animals (sometimes credited for the tufts of yeren “fur” found by locals). The museum urges visitors to explore the forests further, claiming that there are still many discoveries yet to be made, a message that likely resonates with pragmatic officials and amateur enthusiasts alike.

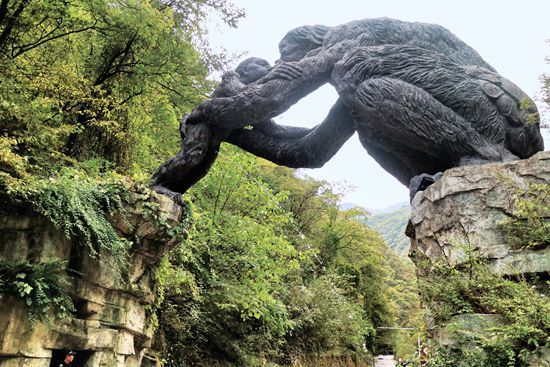

Science lessons aside, there is an almost whimsical nature to the yeren that’s presented to tourists. The gate at Guanmen Mountain, made up of miniature metal cut-outs of the hominid, features a 10-meter-tall statue of a female yeren giving her infant a kiss—tarry a while, and the gatekeeper may even surprise you by pulling a hidden lever that makes the baby yeren “urinate” leftover rainwater, giving any vehicles underneath an impromptu wash.

A statue of a baby yeren “urinating”rainwater at the gate of Guanmen Mountain (Emily Conrad)

These fanciful portrayals are amplified by the magic of Shennongjia forest, where traces of civilization are few and far between, and mountain roads perilously wind around dizzying cliffs, corroded rock faces, and roaring waterways. “Have you looked around at our forests?” I overheard a visitor asking her companions at dinner. “If a yeren could be anywhere in China, it would be here.”

The logic of this argument has resonated with many who have made it their life mission to discover the yeren. An independently funded, volunteer-run “Hubei Wild Man Research Association” organized expeditions in 2010, which proved as inconclusive as the CAS one. Perhaps most famously, an amateur explorer named Zhang Jinxing spent over two decades living in Shennongjia as a hermit, vowing to keep growing his beard until he was successful in finding Hubei’s Bigfoot.

But the Shanxi native recently left the forest mysteriously, closing down his private yeren museum. “It is quite a pity,” our guide, Fu Rao, noted. “He spent so many years dedicated to Shennongjia, researching the yeren, yet he was never able to realize his life dream of seeing one for himself.” What had happened to Zhang? Some reports claim he only ever found hairs, feces, and footprints.

In 2016, though, Zhang told the Global Times that he had in fact encountered yeren several times in the wilderness, but was hesitant to share his so-called discovery with the world. “Once I make it known,” he asked, somewhat theatrically, “will the yeren still be able to live freely and peacefully?”

Where the Wild Things Are is a story from our issue, “Curiosities and Quests.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.